Tax Considerations for Retailers and Manufacturers

The phenomenon of dropshipping — a retail strategy in which sellers do not actually stock any products, instead shipping purchased goods to consumers directly from third-party suppliers — is becoming increasingly prevalent in the ecommerce space. According to one research firm’s analysis, the global dropshipping market size is expected to grow at a rate of nearly 30% per year over the next five years, reaching an expected $200 billion by 2026.

Retailers like dropshipping because it essentially eliminates the costs of warehousing, logistics and distribution. To be a successful dropshipper seller, all you need to have is a market with demand for certain goods and the means to procure those goods. Manufacturers, likewise, can benefit from dropshipping because it allows them to sell their products in new markets without investing in marketing or sales programs.

One major challenge associated with dropshipping, however, is staying in compliance with state and local tax (SALT) obligations — particularly in the wake of the Supreme Court’s ruling in South Dakota v. Wayfair (2018), which radically expanded the conditions under which companies may owe sales and income taxes in states where they do not have a physical presence.

The critical question for most businesses involved in dropshipping — whether they are the party that does the dropshipping or the business that makes use of it — may just be: Who is legally responsible to collect and remit the sales tax?

With the exception of Alaska, Delaware, Montana, New Hampshire and Oregon, each state in the union, as well as the District of Columbia and the territories of Guam and Puerto Rico, imposes some kind of tax on the sale or lease of certain goods and services. Many local jurisdictions also impose sales taxes for revenue.

Under normal circumstances in addition to a physical presence, any business that makes qualifying sales in a given state above a certain dollar amount or a certain number of transactions threshold is required to collect and remit sales tax to the state tax collector.

The two thresholds function as proxies for states to determine which entities have a taxable presence, or “nexus,” in a given state (which is required constitutionally for states to levy taxes on out-of-state businesses).

Supreme Court decisions from the 1960s through the 1990s ensured for many decades that businesses could only be subject to sales tax collections and remittance obligations if they had a substantial physical presence in the state (although the debate regarding whether to impose tax collection obligations on out-of-state merchants has been the subject of spirited debate since the rise of ecommerce in the late 1990s).

It was the 2018 Wayfair ruling, referenced above, that allowed states to add new “economic nexus” laws to the physical presence standard, wherein businesses need only reach a certain number of transactions or exceed a certain dollar amount of sales in the state to be subject to sales tax collection and remittance obligations.

The practice of dropshipping dramatically complicates that arrangement. Obviously, if a seller has sales tax nexus in a given state, they must collect the sales tax due, regardless of whether they use dropshipping or not. But business transactions are not always that simple to analyze in the sales tax world.

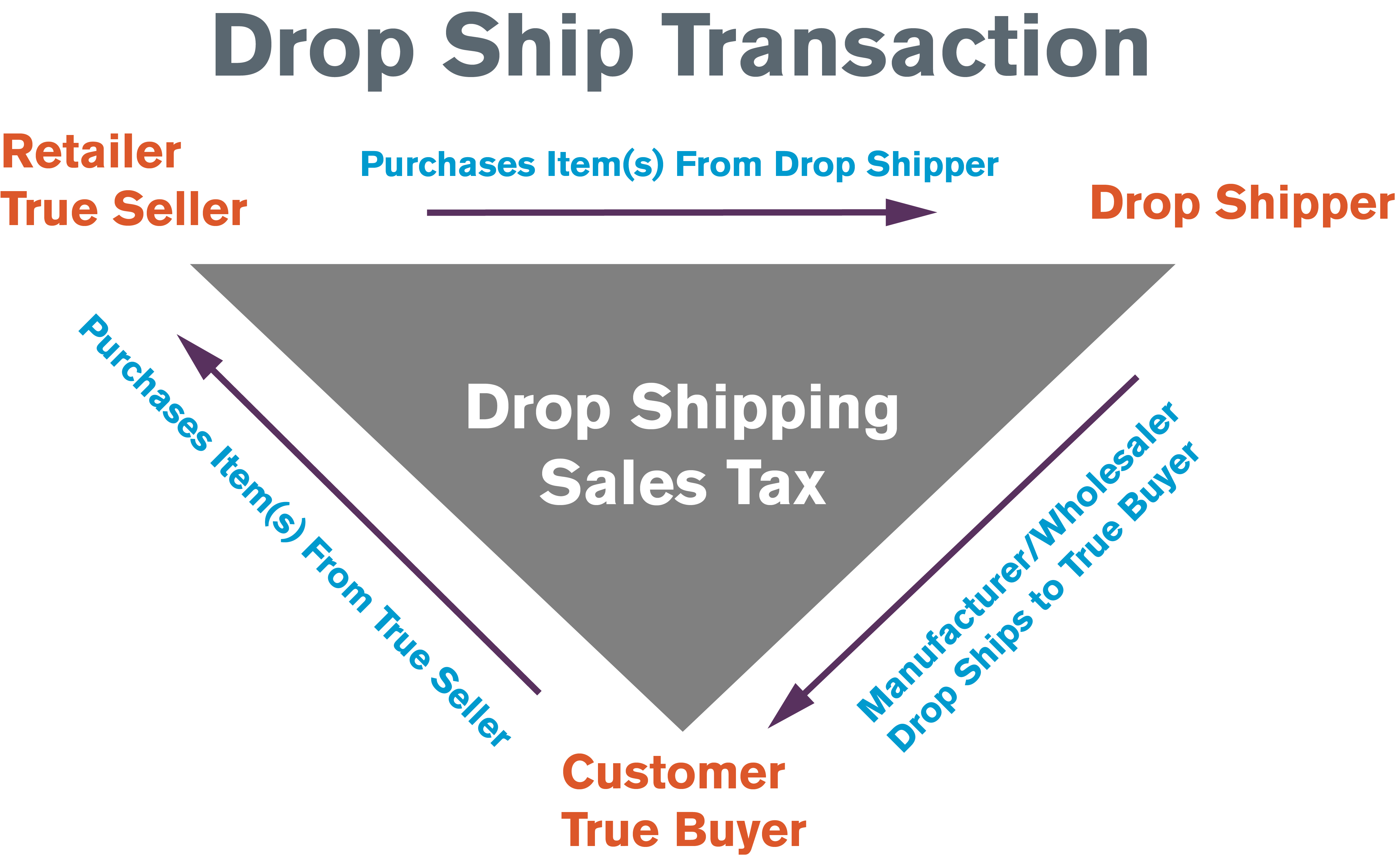

First, note in dropshipping transactions, three parties are involved: Call them “the true seller,” “the true buyer,” and “the dropshipper.” Figure 1 illustrates this triangular relationship. The true seller pays the dropshipper (typically a wholesaler or manufacturer) for the product after the true seller makes the sale to the “true buyer” (i.e., the consumer) — hopefully at a markup — but they never actually take physical possession of the item.

Nevertheless, if the dropshipper delivers (using South Dakota’s economic nexus laws as an example) more than 200 times or $100,000 worth of orders to a true buyer in South Dakota on behalf of an out-of-state true seller, the true seller — not the dropshipper — is required to collect sales tax on those orders having created economic nexus. But the dropshipper may still be responsible for the collection of sales tax on the first 200 transactions or the first $100,000 of sales depending on its own nexus status with the buyer’s state.

It gets trickier when the true seller does not have physical nexus and does not create economic nexus in a state through its dropshipper sales in the designated period. In that case, if the dropshipper has nexus, then the dropshipper may have the legal obligation to collect sales tax for its sale to the true seller depending on the sales tax law in the true buyer’s state.

Figure 1: Drop Shipment Orders

Depending on who ends up collecting and remitting the sales tax due, if any, a valid resale exemption certificate (issued by the state) may need to be exchanged to avoid double taxation on the transaction. And what about the true seller’s mark-up? Should or shouldn’t it be subject to sales tax? That answer varies from state-to-state, like most sales tax questions.

It gets even more weird when neither the true seller nor the dropshipper has nexus, and the dropshipper did not did not deliver more than $100,000 in sales or engage in 200 or more deliveries in the state on behalf of the true seller, to maintain no nexus status for both parties.

In that case, the true buyer/customer is actually responsible for paying use tax — a type of tax that unsurprisingly remains relatively obscure to the general public. A use tax is imposed on the customer for use of the delivered property when they did not pay sales tax to the seller at the time of purchase. Studies on the matter show most consumers do not actually know about use tax, much less actually pay it, even when they are technically required to do so by state and local law.

The above discussion, which uses South Dakota as an example, should not be applied universally, and this blog is by no means 100% comprehensive on the subject of dropshipping taxes. While most states have modeled their economic nexus laws after South Dakota’s, there are important difference between states. Additionally, due to the lack of uniformity in the state’s dropship laws, the dropshipping picture can also be complicated when, for instance, retailers sell to customers who are tax-exempt, or when other exemptions apply in some states, but not all states, that impose sales taxes.

The upshot is that U.S. businesses making substantial sales in multiple states or territories — even when these sales are drop shipment orders and the business otherwise has no nexus in those states or territories — must be extremely careful to track every purchase by its destination to ensure they are in compliance with state sales tax requirements. But, if all this seems a bit overwhelming, do not despair.

Dropshipping is a complicated sales tax topic, even for seasoned ecommerce leaders. That is why if you are in the dropshipment space it is so important that you have an accountant with SALT experience as your trusted tax advisor.

The certified tax professionals in BPM’s State and Local Taxes (SALT) group are standing by to assist businesses that rely on or support dropshipment arrangements. A process both complex and time-consuming, staying in compliance with state sales taxes can comprise a huge portion of these companies’ tax and administrative burdens.

BPM’s SALT team has extensive experience assisting ecommerce businesses that operate across multiple counties and states stay in compliance, helping them avoiding penalties and overpayment alike. With the help of BPM's tax team, you can pay your tax liabilities in the most efficient manner possible. To learn more, visit https://www.bpmcpa.com/Services/Corporate-Tax-Services/State-Local-Taxes.